The war in Europe had been raging for almost three years when America entered in April of 1917. Neutrality had been stressed for so long, President Wilson’s reelection the previous November had hinged on the fact that he had kept the country out of war. Yet when increased German submarine warfare against American ships made the flow of trade questionable, and the boost the war had brought to the American economy was endangered, the powers that be decided they could no longer afford to stay out.

However, it proved to be a challenge to shift popular sentiment and simply declaring war did not bring support from the population at large. It was estimated that one million men were needed to fight and yet in the first six weeks, only 73,000 enlisted. The draft was instituted, and the government created an unprecedented propaganda campaign.[i]

Raising taxes only went so far to finance the war effort so the first Liberty Loan Act was passed April 24, 1917. The idea was to get the general citizenry to invest in war bonds, even in small amounts, and they would be repaid, albeit at a relatively low interest rate, after the war was won.

When the results of the first two bond drives proved disappointing, Treasury Secretary William McAdoo reached out to Hollywood for help. Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin and Douglas Fairbanks all agreed to jump on the band wagon. Adolph Zukor was named to head the committee on Bond Subscriptions and immediately pledged that Famous Players Lasky would buy $100,000 worth of bonds. No one was going to be more patriotic than the film industry which was lead primarily by immigrants.

When the results of the first two bond drives proved disappointing, Treasury Secretary William McAdoo reached out to Hollywood for help. Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin and Douglas Fairbanks all agreed to jump on the band wagon. Adolph Zukor was named to head the committee on Bond Subscriptions and immediately pledged that Famous Players Lasky would buy $100,000 worth of bonds. No one was going to be more patriotic than the film industry which was lead primarily by immigrants.

One of few dissenting voices came from Charlotte Pickford. First and foremost, she was afraid of the crowds, and she did not think Mary’s image needed polishing. They were carefully riding the crest of a perfect wave: “Our Mary’s” picture was everywhere, her films were making a fortune and she was already doing, in Charlotte’s mind, more than enough for the war effort. She also knew that her daughter was already in love with Doug and traveling and appearing together risked a potential public relations disaster.

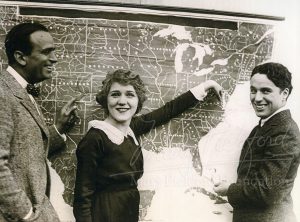

They were going anyway, so Charlotte was on board the train, along with Mary, Charlie, Doug and a small entourage, when it left Los Angeles on April 1, 1918, almost a year after the US had entered what was now called The World War. Their first major rally was scheduled for Chicago, but at every train stop along the way, one of the stars went out on the rear observation platform to speak to the gathered throngs. The Chicago rallies produced crowds like they had never seen gathered in one place before. (See Donald Ogden Stewart’s experience with Mary at Marshall Field’s department store.) They had seen packed theaters and lines outside the box office for their films, but thousands of people showing up for just a glimpse made them realize the full power of their fame for the first time.

They were going anyway, so Charlotte was on board the train, along with Mary, Charlie, Doug and a small entourage, when it left Los Angeles on April 1, 1918, almost a year after the US had entered what was now called The World War. Their first major rally was scheduled for Chicago, but at every train stop along the way, one of the stars went out on the rear observation platform to speak to the gathered throngs. The Chicago rallies produced crowds like they had never seen gathered in one place before. (See Donald Ogden Stewart’s experience with Mary at Marshall Field’s department store.) They had seen packed theaters and lines outside the box office for their films, but thousands of people showing up for just a glimpse made them realize the full power of their fame for the first time.

By the time the “Three Star Special” train departed for Washington D.C., they were all exhausted. Still, along the way, they continued their routine of rotating their role as speakers at the small towns along the route, no matter what time of day or night.[ii]

April 6 brought them to Washington DC where they were joined by Broadway star Marie Dressler for a parade down Pennsylvania Avenue and a reception at the White House. The bond rally that afternoon was held at the Capitol Plaza where it was reported that then Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Franklin D. Roosevelt, bought the first bond.[iii]

It was on to Manhattan where Mary even sold a lock of her curls for the cause. Everywhere they went, together or individually, to speak at rallies – Uptown, Midtown and the Financial District – the crowds they attracted were reported to be “unprecedented.”[iv]

It was on to Manhattan where Mary even sold a lock of her curls for the cause. Everywhere they went, together or individually, to speak at rallies – Uptown, Midtown and the Financial District – the crowds they attracted were reported to be “unprecedented.”[iv]

After their heady experience in New York, the three stars separated and went to different parts of the country to continue selling bonds. By the time Mary returned to Los Angeles, she was declared “Uncle Sam’s most successful saleswoman” with reports that she was responsible for selling as much as 40 million dollars in bonds.[v]

When a fourth Liberty Bond Act was passed in the fall of 1918, Mary took to the road again, but this time stayed in California. She returned to San Francisco where she had sold over 2 million in bonds only months earlier and it was reported she attended as many as a dozen events in a single day. She was joined again by Marie Dressler for a rally in Union Square and then was greeted by 5000 Bethlehem Shipbuilding workers at their plant. She challenged Oakland’s citizenry to compete with other cities to see who could buy the most bonds and encouraged them by contributing $5,000 of her own money to their war bond fund.[vi]

On the train home, Mary stopped at small towns such as Visalia and Fresno, for rallies and speeches and returned to Los Angeles in time to join D.W. Griffith, Lois Weber and other film luminaries for a big rally to celebrate the 4th Liberty Loan Drive on October 19, 1918.[vii]

On the train home, Mary stopped at small towns such as Visalia and Fresno, for rallies and speeches and returned to Los Angeles in time to join D.W. Griffith, Lois Weber and other film luminaries for a big rally to celebrate the 4th Liberty Loan Drive on October 19, 1918.[vii]

In less than a month, the war would be over, and they would be facing a new threat of a flu epidemic. By the time Armistice was declared in November of 1918, America had changed in many ways. “Patriotism” had been successfully capitalized and Mary, Doug and Charlie were more famous and popular than ever. Mary and Doug were also more in love than ever, but that’s another story.

Sources

[i]. Records of the National Archives, the Committee on Public Information; Enlistment numbers from Zinn, A People’s History, page 355.

[ii] Goessel, p 182

[iii] Washington Post 5/7/18

[iv] Goessel p 185

[v] 40 million, Houston Press 10/14/18; “Uncle Sam’s, Oakland Tribune 10/8/18

[vi] dozen events, LA Times, 10/15/18; 2 million, SF Chronicle 10/8/18; Bethlehem and $5,000, SF Chronicle 10/10/18

[vii] LA Times 10/20/18