Mary Pickford willingly returned to Biograph and D.W. Griffith in early 1912, but she was now a married woman of nineteen and a much more self-assured actress. She had never been short of confidence in herself, but at IMP and Majestic, Mary had asserted herself and let her opinions be known in ways unfamiliar at Biograph. Now she raised questions with Griffith and tensions occasionally boiled to the surface. Adding to the strains between them was the fact that during Mary’s absence from the studio, he had hired other beautiful and talented young women such as Mae Marsh and Blanche Sweet who were ready to step into parts Mary balked at playing.

Among the films that Mary made during this time was Lena and the Geese and it would change the lives of friends from several years before, Lillian and Dorothy Gish. The Gish girls, along with their mother Mary, supported themselves acting in touring companies and that’s how they had first met the Smiths, as Charlotte and her brood were still calling themselves at the time. The Gishes’ father had made himself scarce when the girls were very young and they had shared an apartment with the Smiths one summer when money was particularly tight. While Lillian was only a year and half younger than Mary, she remembered her friend as being “like a little mother to us. There was never any question when she told us to do something. We did it.” In early 1912, Lillian and Dorothy had left the stage and were going to school in St. Louis while their mother ran a sweet shop next door to a nickelodeon. It was there that the girls saw Lena and the Geese and recognized their old friend Gladys. Lillian and Dorothy insisted their mother see the film to confirm it was their old friend and they all agreed to look her up when they were next in New York. The address of the Biograph Company was listed in the New York directory, but when they arrived, no one seemed to know a Miss Gladys Smith. When Lillian insisted she had starred in Lena and the Geese, the man in the foyer said, “Oh, you mean ‘Little Mary'” and the friends were reunited. Mary regaled the girls and their mother with stories of the financial rewards of making movies that included the family’s large apartment and a car. When Mary introduced them to D.W. Griffith, he was enchanted and hired Lillian and Dorothy on the spot.

Among the films that Mary made during this time was Lena and the Geese and it would change the lives of friends from several years before, Lillian and Dorothy Gish. The Gish girls, along with their mother Mary, supported themselves acting in touring companies and that’s how they had first met the Smiths, as Charlotte and her brood were still calling themselves at the time. The Gishes’ father had made himself scarce when the girls were very young and they had shared an apartment with the Smiths one summer when money was particularly tight. While Lillian was only a year and half younger than Mary, she remembered her friend as being “like a little mother to us. There was never any question when she told us to do something. We did it.” In early 1912, Lillian and Dorothy had left the stage and were going to school in St. Louis while their mother ran a sweet shop next door to a nickelodeon. It was there that the girls saw Lena and the Geese and recognized their old friend Gladys. Lillian and Dorothy insisted their mother see the film to confirm it was their old friend and they all agreed to look her up when they were next in New York. The address of the Biograph Company was listed in the New York directory, but when they arrived, no one seemed to know a Miss Gladys Smith. When Lillian insisted she had starred in Lena and the Geese, the man in the foyer said, “Oh, you mean ‘Little Mary'” and the friends were reunited. Mary regaled the girls and their mother with stories of the financial rewards of making movies that included the family’s large apartment and a car. When Mary introduced them to D.W. Griffith, he was enchanted and hired Lillian and Dorothy on the spot.

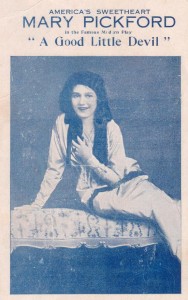

Mary had been working in front of a camera close to nonstop for three years now and itched for a change. She recalled that it was with some trepidation that she reached out to William Dean, David Belasco’s manager, and was thrilled when he told her they had been “looking all over the place” for her. Still referring to her as Betty Warren from her role in The Warrens of Virginia several years before, Dean asked her to come to the theater where he subjected her to a bit of harassment for having been a “very naughty little girl” by appearing in movies. Belasco, however, remembered their reunion differently, saying he knew exactly how to find Mary because by 1912 she was known everywhere as “The Queen on the Movies.” He claimed that he thought of casting her as the blind Juliet in A Good Little Devil the first time he read the play and when he handed her the script, they were a week away from starting rehearsals. Of course Mary jumped at the idea of returning to the stage, making the same two hundred a week she was now getting at Biograph, but she said she needed to talk to Mr. Griffith before formally accepting Belasco’s offer. Pickford remembered that both she and the director had tears in their eyes when she told him she was leaving Biograph. There was still a week until she had to report for rehearsals and so she agreed to make one more film. The New York Hat, co-starring a very young Lionel Barrymore and featuring Lillian Gish in the crowd scene, would go down in Hollywood history as the first screenplay written by Anita Loos who went on to fame as the author of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, but at the time was just an ambitious teenager in San Diego.

Mary had been working in front of a camera close to nonstop for three years now and itched for a change. She recalled that it was with some trepidation that she reached out to William Dean, David Belasco’s manager, and was thrilled when he told her they had been “looking all over the place” for her. Still referring to her as Betty Warren from her role in The Warrens of Virginia several years before, Dean asked her to come to the theater where he subjected her to a bit of harassment for having been a “very naughty little girl” by appearing in movies. Belasco, however, remembered their reunion differently, saying he knew exactly how to find Mary because by 1912 she was known everywhere as “The Queen on the Movies.” He claimed that he thought of casting her as the blind Juliet in A Good Little Devil the first time he read the play and when he handed her the script, they were a week away from starting rehearsals. Of course Mary jumped at the idea of returning to the stage, making the same two hundred a week she was now getting at Biograph, but she said she needed to talk to Mr. Griffith before formally accepting Belasco’s offer. Pickford remembered that both she and the director had tears in their eyes when she told him she was leaving Biograph. There was still a week until she had to report for rehearsals and so she agreed to make one more film. The New York Hat, co-starring a very young Lionel Barrymore and featuring Lillian Gish in the crowd scene, would go down in Hollywood history as the first screenplay written by Anita Loos who went on to fame as the author of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, but at the time was just an ambitious teenager in San Diego.

When A Good Little Devil opened in Philadelphia, D.W. Griffith and many members of the Biograph Company were in the audience. Mary said that Griffith was more nervous than she was and he not only approved of her performance, but gave her his blessings. And when A Good Little Devil opened on Broadway, one of the frequent audience members was one Adolph Zukor.

When A Good Little Devil opened in Philadelphia, D.W. Griffith and many members of the Biograph Company were in the audience. Mary said that Griffith was more nervous than she was and he not only approved of her performance, but gave her his blessings. And when A Good Little Devil opened on Broadway, one of the frequent audience members was one Adolph Zukor.

Adolph Zukor had immigrated to America as a sixteen-year-old Hungarian orphan. He had immersed himself in the culture of his new country and risen to become a very successful furrier when, in 1903, he invested in arcades with machines where, by putting in coins and peering into a box, customers could watch dramas lasting half a minute. Initially, Zukor thought of the arcades as an aside to his fur business, but he soon found himself fascinated by the new phenomenon of movies and expanded to nickelodeons.  Zukor saw a future in longer films when one-reelers were still being used to clear out theaters between vaudeville performances and became convinced, as one of his biographers put it, “that the movies only seemed like novelties because they were treated like novelties.” Unable to convince his contemporaries such as Marcus Loew or Carl Laemmle to share his vision, Zukor bought the American rights to a French film, Queen Elizabeth, starring Sarah Bernhardt and, by carefully screening the almost hour-long film as a stage production and distributing it state by state, Zukor quadrupled his investment. He joined forces with New York producer Daniel Frohman to create Famous Players Film Company with its slogan “Famous Players in Famous Plays.” Minnie Maddern Fiske, the grande dame of the American stage, was filmed in Tess of the D’Urbervilles and Lilly Langtry starred in His Neighbor’s Wife. Because of the interest in the hinterlands to see these famed actresses, the hour-long movies were fairly successful, but filmed stage plays were just that. They didn’t “move” like the one and two-reelers and of course the audience could not hear the voices. Still, Zukor stayed true to his vision and it was natural that he would come calling on Broadway’s premiere producer, David Belasco. Stalking was more like it, for Zukor became a fixture at the theater until finally Belasco agreed to sell him the rights to film A Good Little Devil starring its New York cast.

Zukor saw a future in longer films when one-reelers were still being used to clear out theaters between vaudeville performances and became convinced, as one of his biographers put it, “that the movies only seemed like novelties because they were treated like novelties.” Unable to convince his contemporaries such as Marcus Loew or Carl Laemmle to share his vision, Zukor bought the American rights to a French film, Queen Elizabeth, starring Sarah Bernhardt and, by carefully screening the almost hour-long film as a stage production and distributing it state by state, Zukor quadrupled his investment. He joined forces with New York producer Daniel Frohman to create Famous Players Film Company with its slogan “Famous Players in Famous Plays.” Minnie Maddern Fiske, the grande dame of the American stage, was filmed in Tess of the D’Urbervilles and Lilly Langtry starred in His Neighbor’s Wife. Because of the interest in the hinterlands to see these famed actresses, the hour-long movies were fairly successful, but filmed stage plays were just that. They didn’t “move” like the one and two-reelers and of course the audience could not hear the voices. Still, Zukor stayed true to his vision and it was natural that he would come calling on Broadway’s premiere producer, David Belasco. Stalking was more like it, for Zukor became a fixture at the theater until finally Belasco agreed to sell him the rights to film A Good Little Devil starring its New York cast.

According to Zukor, Belasco warned him that Mary Pickford might not be willing to go before the cameras again, claiming “Mary was ashamed, you know, to come back to me after appearing on the screen.” Zukor, however, sensed that respect and money spoke loudly to the Pickfords and invited Charlotte and Mary to dine with him at Delmonico’s. Sure enough, after listening to his speech about his belief in feature films and the public’s desire to see famous plays, Charlotte had one question: “What salary would you consider paying Mary?” When he suggested several hundred a week with promises of more to come, Mary ended the conversation by saying, “We’ll talk it over.”

According to Linda Griffith, D.W.’s wife who wrote an occasionally accurate account of this time, it was then that Mary and Charlotte returned to E. 14th Street and, as Linda put it, “Mary and Mother bearded the lion in his den” and the following conversation took place.

According to Linda Griffith, D.W.’s wife who wrote an occasionally accurate account of this time, it was then that Mary and Charlotte returned to E. 14th Street and, as Linda put it, “Mary and Mother bearded the lion in his den” and the following conversation took place.

“Well, what are you asking now?” queried Mr. Griffith.

“Five hundred a week,” answered Mrs. Smith.

“Can’t see it. Mary’s not worth it to me.”

“Well, we’ve been offered five hundred dollars a week and we’re going to accept the contract, and you’ll be sorry one day.”

Linda concludes the story with “They could go ahead and accept the contract as far as Mr. Griffith was concerned. Indulging in his old habit of walking away while talking, he brought the interview to an end, calling back to the insistent mother, ‘Three hundred dollars is all I’ll give her. Remember, I made her.’” And Linda Griffith adds, “But whether Mr. Griffith has ever been sorry, nobody knows but himself.”

Whatever the string of events and the accuracy of the recounted conversations, Mary Pickford signed with the Famous Players at $500 a week shortly thereafter. Zukor said it was for a year, Mary remembered fourteen weeks, but we know that six months later, she was making $1,000 a week. After filming A Good Little Devil and two other films, Mary and the Famous Players company headed to Los Angeles.

Whatever the string of events and the accuracy of the recounted conversations, Mary Pickford signed with the Famous Players at $500 a week shortly thereafter. Zukor said it was for a year, Mary remembered fourteen weeks, but we know that six months later, she was making $1,000 a week. After filming A Good Little Devil and two other films, Mary and the Famous Players company headed to Los Angeles.