Today, when D.W. Griffith’s name is mentioned, many people think only of the technically brilliant and shockingly racist The Birth of a Nation. In fact, in 1999 the Director’s Guild of America changed the name of their annual D.W. Griffith Award, initiated in the 1950s, to simply Lifetime Achievement Award because, as their president Jack Shea explained, “As we approach a new millennium, the time is right to create a new ultimate honor for film directors that better reflects the sensibilities of our society at this time in our national history.”

Griffith, however, directed over 450 films, including Intolerance, Broken Blossoms and many others that pushed creative barriers. And of course he was Mary Pickford’s first film director. His place in film history can be illuminated by testimonies from his contemporaries, people who knew Griffith and worked with him before he made The Birth of a Nation, and what follows are a few samples of the ways in which he inspired other filmmakers, their casts and crews.

Allan Dwan, the great director of over 100 silent and sound films known for such epics as Robin Hood (1922), spoke about how he learned to make movies in the first place:

Allan Dwan, the great director of over 100 silent and sound films known for such epics as Robin Hood (1922), spoke about how he learned to make movies in the first place:

“I had to learn from the screen. I had no other model…The only man I ever watched was Griffith and I just did what he did. It was a wonderful, successful thing to do. I’d see his pictures and go back and make them at my company… Biograph was by many miles the best and the most popular because of Griffith. His pictures had good photography, good lighting, good everything and by watching what he was doing, you learned. We were completely alone you see – there was nobody to talk to, no one to compare with.”

When asked to be specific about what he learned from Griffith, Dwan added:

“One of the most important things was economy of gesture, which to me is a very important portion of the act of acting. To do a great deal with very little in terms of motion… Sometimes the most silent scene with the least gesture provokes the great emotion in the audience. Then I also like the use of the close-up which Griffith introduced, the back lighting he used extensively rather than letting the sun blaze at the actors directly, his side lighting and his compositions in general. He was superb. The principal thing was the lighting.”[i]

Cecil B. DeMille called Griffith “a great genius” and said:

“He was the teacher of us all. Not a picture has been made since his time that does not bear some trace of his influence. He did not invent the close-up or some of the other devices with which he has sometimes been credited, but he discovered and he taught everyone else how to use them for more beautiful effect and better story telling on the screen.”[ii]

Mickey Neilan, who Mary Pickford often referred to as her favorite director, bemoaned the “old problem” of coming up with new story ideas because Griffith seemed to have already made them all. Neilan and Griffith met while they were both actors in a touring company in 1906 and they stayed friends until Griffith’s death in 1948. Neilan described Griffith as:

“A well built six footer graceful in action, he was the type of man you would look at once and say, ‘actor’ – long hair and long nose. Piercing eyes and the most wonderful voice I ever heard in a human being. It had a pipe organ quality and he knew how to pull and shut the stops to control it.”[iii]

Neilan cites many reasons he respected Griffith as a filmmaker and what traits made him so accomplished. For example, Neilan said:

“D.W. Griffith, in one of our many, many chats, said that one or two of the greatest assets valuable to a motion picture director was to be born with a retentive memory. A keen sense of observation to be able to study characters, watch their mannerisms and habits and be able to file the same away for future use in directing your cast. He was so absolutely right.”

Neilan also credited Griffith with “inventing” previewing films:

“Only Griffith gave previews allowing in the public. He was the originator of the preview, only he didn’t hand out the cards asking for audience criticisms. His previews were simply to get audience reaction while watching his pictures and furthermore, he held all his previews well out of Hollywood where the public were not so picture wise.”[iv]

Lillian Gish was, along with her sister Dorothy, introduced to Griffith by their childhood friend Mary Pickford. Lillian went on to star in many of his most successful films including The Birth of A Nation, Intolerance and Broken Blossoms and while she stayed with him longer than most actors, she observed his attitude towards other stars when they moved on.

Lillian Gish was, along with her sister Dorothy, introduced to Griffith by their childhood friend Mary Pickford. Lillian went on to star in many of his most successful films including The Birth of A Nation, Intolerance and Broken Blossoms and while she stayed with him longer than most actors, she observed his attitude towards other stars when they moved on.

“He had an ambivalent attitude toward his protégées. He helped them achieve success, and when they wanted to leave, he let them go without a restraining word. He was happy for this. His satisfaction at Mary [Pickford’s] success – and later that of Richard Barthelmess, Mae Marsh and others – was genuine and spontaneous. He never clutched at anyone.”[v]

Raoul Walsh would become an acclaimed director, but he was an actor working with Pathé in 1914 “feeling more foolish each night” because of “the god-awful stuff Pathé was making.” When he was offered a job at Biograph, he was thrilled because he thought “both the directing and the acting seemed superior to anything I had so far experienced.” Once there, Walsh learned that Griffith was leaving Biograph and was going to head to the coast to start a new company and Walsh signed up to make the trip.[vi]

Walsh summarized his several years of experience working with Griffith in California as follows:

“D.W. Griffith was a genius when it came to making a motion picture. He was a quiet man, almost shy until he picked up a megaphone. He called every male member of the company ‘Mister’ and discouraged familiarity. Some of his biographers have accused him of arrogance and unfairness for being ‘Mr. Unapproachable.’ I always found him ready to listen to opinions, and he was the first to offer help when any of his people got into trouble. Whenever I had the chance, I watched while he directed, and tried to remember everything he said and did. Not many people are lucky enough to have a genius for a teacher and the lessons were free. All I needed to do was keep my eyes and ears open.

Later, when I became a director myself, I profited greatly from the things this master taught me. Cabanne and the other Fine Art directors were all competent, but none of them had the touch and the superb sense of the dramatic which were evident in everything Griffith made. When he produced and personally directed The Birth of a Nation, the world acclaimed his artistry and paid belated tribute. This spectacle changed the history of movies and for the first time put them on a par with all other forms of art. And its nationwide box office success made movies big business.”[vii]

Anita Loos first came to Hollywood in 1915 to work for Griffith and went on to become the acclaimed author of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, but she was a high-school student in San Diego where her father ran a theater when, in 1912, she first came in contact with Griffith’s work. At that time, Anita and her sister Gladys often acted in their father’s theater where short films were shown between performances.

Anita Loos first came to Hollywood in 1915 to work for Griffith and went on to become the acclaimed author of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, but she was a high-school student in San Diego where her father ran a theater when, in 1912, she first came in contact with Griffith’s work. At that time, Anita and her sister Gladys often acted in their father’s theater where short films were shown between performances.

“I adored those old silent films, knew the particular style of each company – Selig, Vitagraph, Kalem and, best of all, Biograph, which produced more literate stories played by a more sensitive group of actors. Nobody was aware of the young director, D.W. Griffith, who was solely responsible for the fact that Biograph movies were so much more imaginative and, at the same time, real than all the others.

Pop, in booking his films, took all the Biograph pictures and I would hurry with my costume changes to get down to the dark stage, where I could see them from the reverse side of the screen, with the light of the projector casting a bright splotch in the middle. On a certain night, while entranced by one those movies, I realized that it had required a script, so I decided to try my hand at writing one. The next morning I worked out a plot and that afternoon at rehearsal I climbed up into the projection and searched the film cans for an address where I might send my story. The address I found was American Biograph Company, 11 East 14th Street, New York City… Not more than two weeks went by before I received a long envelope with American Biograph Company impressively engraved on the corner. With hands shaking like an earthquake, I tore the envelope apart and reported this letter:

We have accepted your scenario entitled ‘The New York Hat.’ We enclose an assignment which kindly sign and have witnessed by two persons, and then return. On receipt of signed assignment we shall send you our check for $25.00 in payment.”

…And a career was born.[viii]

Hobart Bosworth was an acclaimed Broadway star in the early 1900’s when he was struck with tuberculosis and lost his voice and a third of his weight in the course of three months. He came to California, known for its dry warm weather, to regain his health, thinking his acting days were over, but was approached by the Selig Company in 1909 to act in In the Sultan’s Power with an offer of “more money for two days’ work than I had ever received in my life of devotion to the drama.” It opened a new career for Bosworth as an actor, director and, in 1913, as the founder of his own studio. He sold his company to Paramount in 1916 when his health started to fail again, but he returned to acting and eventually appeared in over 250 films.

“I remember in those days every scene I made I wondered how HE, D.W., would make it, and tried to make it as I thought he would like it done. I think he influenced all of us directors in just that way, but I don’t think that even he, with his great grasp of his medium, knew much more about what he had than we did.”[ix]

Mack Sennett worked as an actor in the Biograph company and went on to create his own studio, the Keystone Cops and to direct hundreds of films with stars such as Charlie Chaplin, Gloria Swanson and Mabel Normand. Sennett didn’t always get along with Griffith for a variety of reasons, yet he learned a lot from him and in his 1954 autobiography, Sennett credited Griffith, who he called “the absolute pioneer of the screen,” with creating the path everyone else followed.

“He, and his cameraman, Billy Bitzer, invented the close-up, ‘Rembrandt’ lighting, and what we now call the ‘idiom’ of the screen. He did that in 1910 and what he did was as fundamental to movies as the wheel is to mechanics. We have widened the screen now, but we are still telling stories the way D.W. Griffith taught us to tell them.

D.W. Griffith, when you come right down to it, invented motion pictures. As Lionel Barrymore says, there ought to be a statue to him at Hollywood and Vine, and it ought to be fifty feet high, solid gold, and floodlighted every night.”[x]

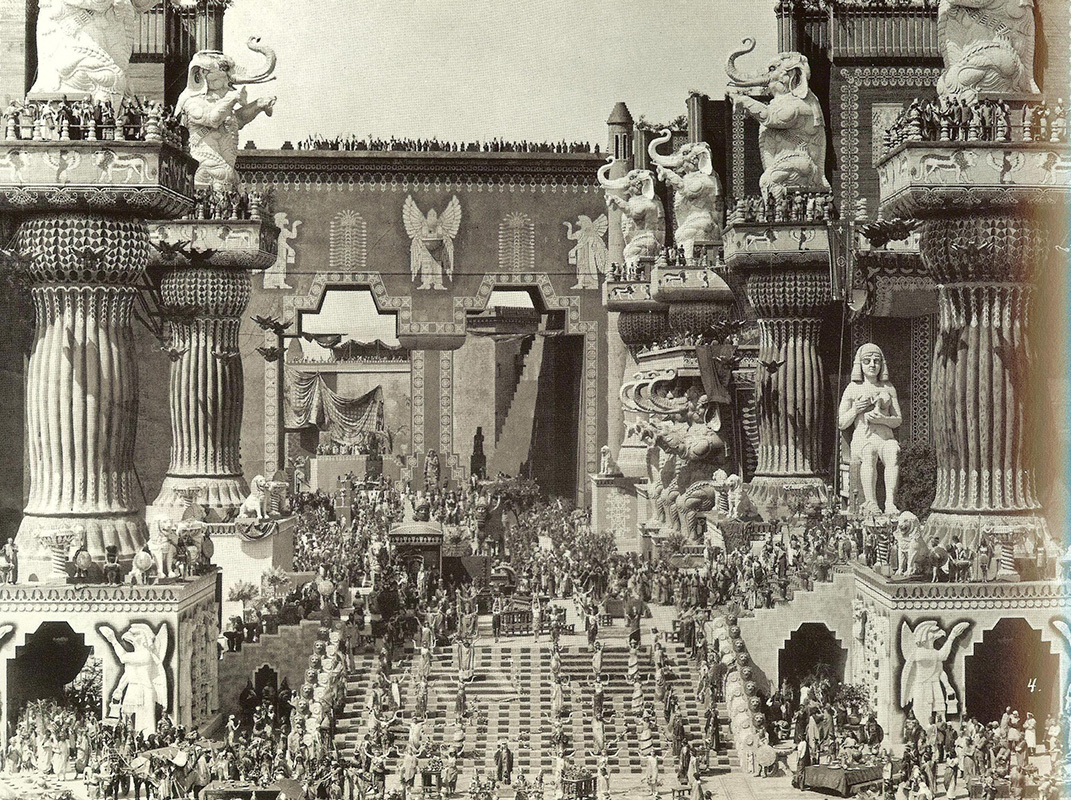

We know there is no statue, but the large elephants atop the mall at Hollywood and Highland serve as an homage, to those few who recognize it, to the great set Griffith constructed nearby for Intolerance. But what becomes clear from these commentaries is that his work rippled out to affect so many others that we will never know the extent of his influence.

Griffith stopped being Mary Pickford’s director in 1913, and soon after that he left (or was pushed out) of Biograph. He joined Mutual where, as he later put it, “It was ‘mutual’ all right. I did the work and they got the profits.” Many people would make a small fortune off of The Birth of a Nation, including Louis B. Mayer who had the New England distribution rights to the film and pocketed so much more than he reported making at the box office that he accumulated enough money to move into film production. However, Griffith was not one of those who profited, paying little attention to finances and focusing instead on his next film.

Pickford and Griffith remained friends and he was one of the four original founders of United Artists in 1919. He made his last film in 1931, died in Los Angeles in July of 1948 and was buried in his native Kentucky. In 1950, Mary made a trip to his gravesite and, joined by Lillian Gish and Richard Barthelmess, placed a regal stone marker provided by the Screen Actors Guild on Griffith’s grave.

[i] Bogdanovich, Peter. Allan Dwan: The Last Pioneer, p. 25

[ii] DeMille, Cecil B. Autobiography of Cecil B. DeMille, p. 125

[iii] Neilen, Marshall. Unpublished memoirs, dated 5/1/1955

[iv] Neilen, Marshall. Unpublished memoirs, dated 9/4/58

[v] Gish, Lillian. The Movies, Mr. Griffith and Me, p. 82

[vi] Walsh, Raoul. Each Man in His Time, p. 69

[vii] Walsh, Raoul. Each Man in His Time, pp. 80-81

[viii] Loos, Anita. A Girl Like I, pp. 55-56

[ix] Bosworth, Hobart, Lecture on Film at USC 2/26/1930

[x] Sennett, Mack. King of Comedy, pp. 54-55