They called themselves United Artists, but the trades called it a “rebellion against established producing and distributing arrangements” when Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks and D.W. Griffith went before the cameras on February 5, 1919 to sign the documents that created the corporation that the filmmakers claimed was necessary to protect their own interests as well as to “protect the exhibitor and the industry from itself.”

It wasn’t any great prescient vision that had brought Hollywood’s biggest money makers to this point. Rather, they were reacting, and quickly, to the what they saw as a threat by producing companies to limit their salaries and the quality of their films.

Pickford, Fairbanks and Chaplin might have volunteered to tour the country selling war bonds for patriotic reasons, but the overwhelming crowds their presence generated gave them a new confidence in their popularity. Why were they giving so much of the profits to producers? After all, didn’t audiences come to the movies to see them, not Zukor or Lasky?

While they were asking themselves those questions, executives at the producing companies were asking themselves why they were paying the stars so much.

A little backstory: During the 1910’s, film production companies, theaters and distribution mechanisms had multiplied and, in retrospect, reaction was often the catalyst for change. Production, Exhibition, Distribution. They were the three legs of the film business and the participants were often in flux. Like so many companies, First National had come into being as a reaction; in this case to Adolph Zukor’s practice of block booking. If theaters wanted Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks films, they had to agree to purchase all of the 100 plus Famous Players films each year, no matter the quality. In response, 26 smaller theater owners banded together in 1917 to buy and distribute films at competitive rates, vowing not to compete against each other. The idea was so successful that a year later, 600 theaters were in the First National cooperative. Then, no longer content just to buy films from others, they created First National Pictures to make their own films. The first big name to sign with them was Mary Pickford, for $1,500,000 a year with “complete artistic control” and D.W. Griffith and Charlie Chaplin soon joined her at First National.

A little backstory: During the 1910’s, film production companies, theaters and distribution mechanisms had multiplied and, in retrospect, reaction was often the catalyst for change. Production, Exhibition, Distribution. They were the three legs of the film business and the participants were often in flux. Like so many companies, First National had come into being as a reaction; in this case to Adolph Zukor’s practice of block booking. If theaters wanted Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks films, they had to agree to purchase all of the 100 plus Famous Players films each year, no matter the quality. In response, 26 smaller theater owners banded together in 1917 to buy and distribute films at competitive rates, vowing not to compete against each other. The idea was so successful that a year later, 600 theaters were in the First National cooperative. Then, no longer content just to buy films from others, they created First National Pictures to make their own films. The first big name to sign with them was Mary Pickford, for $1,500,000 a year with “complete artistic control” and D.W. Griffith and Charlie Chaplin soon joined her at First National.

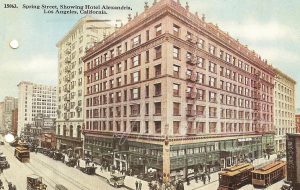

But a few months later, when First National executives were gathering at the Alexandria Hotel in Los Angeles in January of 1919, Chaplin went before them to request a larger budget and was refused. He was indignant. How could you have “complete artistic control” without control of the budget?

But a few months later, when First National executives were gathering at the Alexandria Hotel in Los Angeles in January of 1919, Chaplin went before them to request a larger budget and was refused. He was indignant. How could you have “complete artistic control” without control of the budget?

Still, their complaints and dreams might have remained just that if not for reported rumblings of a merger between the two major distributors, Paramount and First National, in early 1919. Mary had thrived on playing one off against the other to continually increase her income and if such a merger went through, they all knew it would “clamp the lid on the salaries.”

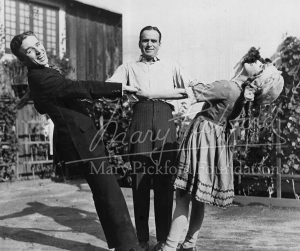

The stars hired the Pinkerton Agency to go undercover at that gathering of First National representatives and when their female agent confirmed the rumors, Doug, Mary, Charlie and Griffith were ready with their own plan. That January, Mary had been felled by the flu, but Charlotte stepped in to take her place at the meeting at Charlie’s brother Sydney’s house where their plans came together. Griffith was there and Doug brought in his and Mary’s attorney Dennis O’Brian and his brother Robert Fairbanks.

Initially, the cowboy star, William S. Hart, was a participant in their plans for a releasing corporation, but when Zukor promised him $200,000 a film without any production headaches or financial commitments, he re-signed with Famous Players.

Initially, the cowboy star, William S. Hart, was a participant in their plans for a releasing corporation, but when Zukor promised him $200,000 a film without any production headaches or financial commitments, he re-signed with Famous Players.

They were committing to put up their own money to produce their own films without hindrance from anyone, including each other. William McAdoo, the former Secretary of the Treasury whom Doug had befriended on the bond tours, was named their General Counsel, adding an air of prestige from outside the industry. McAdoo knew little about making pictures, but in these heady times, Fairbanks, Pickford, Chaplin and Griffith represented the most successful and experienced combine imaginable.

They would face many challenges over the years and, in the mid-twenties, they would bring in Joe Schenck to run the company who in turn brought in his wife, Norma Talmadge, his sister-in-law Constance and their brother-in-law Buster Keaton. Other stars and producers came and went. For Mary, who was already in love with Doug and would marry him the next year, it was not always easy to deal with both a husband and his best friend as business partners. But she proved herself to be an inspired and informed businessperson as she actively helped steer UA from its inception through the early 1950s.

But all that was in the future on that exciting day, February 5, 1919, when the balancing act between production, distribution and exhibition was altered irrevocably by the stars taking control of producing and distributing their own films.