Mary would later say that, as she walked up the stairs of the brownstone at 11 E. 14th Street in 1909, she prayed no one she knew from the theater would see her. It was probably the most famous address in the film business at the time, but she considered “the flickers,” as almost everyone called the movies, lower class entertainment. Yet times were changing quickly; Variety had begun writing about films in 1906 because they were shown in between vaudeville acts to clear out the theaters, but smart managers saw movies’ growing popularity and began opening theaters just for the films. And they were cheaper and more dependable than live acts.

The mansion-turned-Biograph-studio had a large marble-floored foyer where a secretary manned the reception area. One room was set aside as the women’s dressing room and an alcove served as the wardrobe room. Mary said she was “overawed” by the vast circular ballroom that had been transformed into the main studio with lights hung low from the ceiling.

She loved telling the story that when Griffith offered her the standard five dollars a day, she pulled herself to her full five feet and said, “I am a Belasco actress and I must have ten.” He laughingly agreed, but swore her to secrecy because if others in the company knew, he would have “a riot” on his hands. Soon after, she agreed to forty a week with a guarantee of work. Griffith later said, “The thing that most attracted me the day I first saw her was the intelligence that shone in her face,” and he put her to work that very first day. Over the next year, they became a volatile, creative team.

Mary might have been getting ten dollars a day, but the highest paid actress at Biograph at the time was Florence Lawrence and she was making twenty-five a day. No names were in the credits, not even Griffith’s, but Florence Lawrence was popularly referred to as “The Biograph Girl.” Already the quality of Biograph films was becoming known – theaters advertised “Biograph days”to draw a crowd. But shortly after Mary arrived, Florence Lawrence was hired away by Carl Laemmle’s Independent Motion Picture Company with ads that ran “The Biograph Girl is now an IMP.” IMP’s gain was also Mary’s as she picked up the title of “The Biograph Girl.”

Mary might have been getting ten dollars a day, but the highest paid actress at Biograph at the time was Florence Lawrence and she was making twenty-five a day. No names were in the credits, not even Griffith’s, but Florence Lawrence was popularly referred to as “The Biograph Girl.” Already the quality of Biograph films was becoming known – theaters advertised “Biograph days”to draw a crowd. But shortly after Mary arrived, Florence Lawrence was hired away by Carl Laemmle’s Independent Motion Picture Company with ads that ran “The Biograph Girl is now an IMP.” IMP’s gain was also Mary’s as she picked up the title of “The Biograph Girl.”

To Mary, Griffith appeared to be the ultimate authority figure, yet he had only been directing films for less than a year when she arrived. Born on a Kentucky farm, he had moved to Louisville after his father’s death when Griffith was seven. As a young teenager Griffith worked a variety of jobs to help support his mother and six siblings, including acting on the Louisville stage where he claimed he carried a spear for “the divine Sarah Bernhardt.” He was soon on the road, spending more than a decade traveling through the American hinterlands with different stage companies, acting and trying to be writer. To keep the wolf from the door, as he put it, he joined the Bronx-based Edison Company in 1907 and jumped to Biograph the following year. After several months acting and writing, he was approached to direct and, while he needed to be reassured he could return to acting if it didn’t work out, he quickly found his métier. All those years of learning stagecraft, story arcs and characterizations came together and in part because he was so thoroughly immersed in theatrical conventions, he was free to leave some of them behind as his techniques evolved. New as he was in a chronological sense, Griffith had already directed 100 one-reelers by the time Pickford arrived at his doorstep. He was only in his mid-thirties, but he cultivated the airs of a southern gentleman with Victorian manners. At Biograph, one of the first things the 16-year-old Pickford had to get used to was people calling each other by their first names, although no one called D.W. Griffith anything but Mr. Griffith. He, in turn, called her “Pickford” once he started remembering her name.

The Griffith method was to gather his company around him while he sat on the stage, explain the action and then rehearse scenes. Once he was sure everyone knew what was expected, the film was shot. “To stop the camera in those days,” Mary said, “was unheard of.” Wasting film was wasting money; it cost two cents a foot. And in part because Griffith was paid a bonus for every foot of film he produced, movies were turned out quickly. Mary was comfortable with rehearsals, but to get used to playing to the camera instead of an audience, she practiced her expressions in front of a mirror over and over again.

Her years in the theater had taught her to use her entire body to act the part, and this was at a time when close-ups and mid-range shots were unheard of. “I refused to exaggerate in my performances,” Pickford told Kevin Brownlow. “I would not run around like a goose with its head cut off.” While she believed she had to resist Griffith’s desire for her to be more expansive, she gave him full credit for teaching her the little things that made a performance realistic. Mary quoted Griffith as saying she would do anything “for the camera. I could tell her to get up on a burning building and jump – and she would.” While Mary didn’t go quite that far, she acknowledged that “there is something sacred to me about that camera. He once said to me that he could sit back of the camera, think something and I’d do it… I think in his way he loved me, and I loved him.”

Her years in the theater had taught her to use her entire body to act the part, and this was at a time when close-ups and mid-range shots were unheard of. “I refused to exaggerate in my performances,” Pickford told Kevin Brownlow. “I would not run around like a goose with its head cut off.” While she believed she had to resist Griffith’s desire for her to be more expansive, she gave him full credit for teaching her the little things that made a performance realistic. Mary quoted Griffith as saying she would do anything “for the camera. I could tell her to get up on a burning building and jump – and she would.” While Mary didn’t go quite that far, she acknowledged that “there is something sacred to me about that camera. He once said to me that he could sit back of the camera, think something and I’d do it… I think in his way he loved me, and I loved him.”

Mary soaked it all in. As Griffith would later say, “I found she was thirsty for work and information. She could not be driven from the studio while work was going on.” That drive actually evolved; what was at first just a job soon became a passion and she immersed herself in learning every aspect of filmmaking. Mary’s strong sense of professionalism mandated that whatever she did, she was going to do it as well as or better than anyone else. Yet no one worked harder than Griffith. He often started days before dawn heading to a location, spent his afternoons and early evenings shooting interiors at the studio and stayed as late as midnight watching the previous day’s work. However, Mary put in long hours too. She befriended the cameraman Billy Bitzer and together they tested how various make-ups photographed on her as well as the impact of changing the position of the lights, using rudimentary reflectors such as oil cloth and white gravel. The art of filmmaking was advancing on a daily basis and the fact they were working in relative obscurity encouraged experimentation.

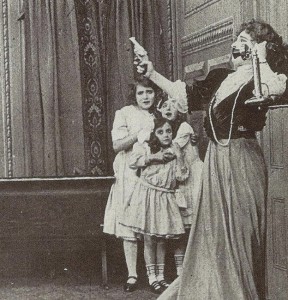

In retrospect, it is easy to see how Griffith and Pickford were learning from and with each other. Griffith is credited with making 138 films in 1909 and Mary was in 45 of them. Together, they broke new ground as they innovated filmmaking; Griffith through camera angles and movement, crosscutting, close-ups and fade-outs and Mary by bringing a naturalness to the screen as she played children, married women, waifs, Native Americans and housemaids. They were both discovering the depth and breadth of their craft and in the process, raising the bar for every other director and actor.

To view some of Mary’s work in these films, click here »

Related Links: