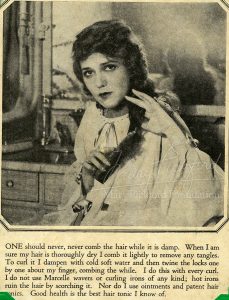

To many in the teens and twenties, Mary Pickford and her golden curls were one, yet she had long been wrestling with the question of whether her famous locks were holding her back. She had consistently given her fans what they wanted; after several attempts at playing grown women, she had returned to playing a young girl in Little Annie Rooney and Sparrows. Mary said that except for bangs when she was a child, scissors had never touched her hair. While others might wash it, Mary usually tended to her hair herself, using leather curling rags after her hair was almost dry. She also insisted she wouldn’t trust anyone to comb her hair, except her mother, because it needed to handled gently to keep the curls in place. Finally, after her mother Charlotte passed away in early 1928, Mary was ready to take action. She was in her mid-thirties and she decided she “couldn’t go on being Rebecca and Tess and Pollyanna and Annie forever. I had to take a courageous stand, once and for all. “

To many in the teens and twenties, Mary Pickford and her golden curls were one, yet she had long been wrestling with the question of whether her famous locks were holding her back. She had consistently given her fans what they wanted; after several attempts at playing grown women, she had returned to playing a young girl in Little Annie Rooney and Sparrows. Mary said that except for bangs when she was a child, scissors had never touched her hair. While others might wash it, Mary usually tended to her hair herself, using leather curling rags after her hair was almost dry. She also insisted she wouldn’t trust anyone to comb her hair, except her mother, because it needed to handled gently to keep the curls in place. Finally, after her mother Charlotte passed away in early 1928, Mary was ready to take action. She was in her mid-thirties and she decided she “couldn’t go on being Rebecca and Tess and Pollyanna and Annie forever. I had to take a courageous stand, once and for all. “

When Mary and Doug stopped in New York as they returned from their annual trip to Europe in June of 1928, Doug was full of plans to make his next film, The Iron Mask. In fact, he had convinced the English set designer Laurence Irving to drop everything and come with them to America and while in France, Doug had hired the designer Maurice Leloir who would follow them shortly. Mary had been quieter about her plans, but once in Manhattan, she secured the rights for the play Coquette. It would be her first “talkie” and she convinced herself that to play the role effectively, she needed short hair.

In her draft manuscript of her autobiography, Mary goes into more detail about deciding to cut her hair than was eventually published in Sunshine and Shadow.

In her draft manuscript of her autobiography, Mary goes into more detail about deciding to cut her hair than was eventually published in Sunshine and Shadow.

They had been my making, those curls, and my unmaking too. They had given my pictures a badge of respectability. They prohibited me from playing anything in the slightest degree censorable. [They were the trademark that made my films safe for children.] Mothers trusted those curls as they trusted their own consciences.

Between that restriction and the weight of the curls, there was little left for me to do and very little ground that I could cover…..[After making Sparrows] I played a little girl for the last time. I was determined now, as I had never been before, to close the door on my screen childhood and to be my age, or something near it.

She told Doug where she was going as she left their suite at the Sherry Netherlands, but he wasn’t sure whether to believe her or not. But even more surprised about her decision was Charles Bock, the stylist whose hair salon was on the corner of 57thand Fifth Ave.

Let Mary take up the story from there where she says she had to assure Bock:

“Are you sure that you are not going to regret this step, Miss Pickford?” he asked.

I replied, “I’m quite sure. I have thought it over again and again. They’ve become a stumbling block to the future of my career.”

“All right; here goes.”

As he gripped the shears I had the feeling he needed aromatic spirits of ammonia more than I did.

The hair cut was deemed so consequential that it made the front page of the New York Times the next day:

After he had carefully cut off the twenty or so ringlets of hair….she gathered them in her lap and pronounced, “Well, they’re gone and I’m glad.” Bock looked over the head of hair in front of him that still reached to her shoulders while Mary told him she didn’t want “a shingle, a bob or anything like that.” He agreed and suggested, “What you want is a long bob, to suit you, the Mary Pickford bob.” And with that the real work began “with precision” to style her remaining hair intro a stylish, still curly cut. With a smile, she took out five dollars from her purse, paid Bock and took her curls with her back to her hotel.

Mary picks up the story once she returned to the Sherry Netherlands:

When I removed my hat and showed Douglas my shorn head, he turned pale, took one step back and fell into a chair, moaning “oh, no, no no.” And great big tears came into his eyes.

“But I told you I was going to do it…”

“I know, Hipper, but I didn’t think you meant it. I never dreamt you’d do it.”

I must have looked very crestfallen over his reaction, for he immediately changed his tune.

“Whatever makes you happy, Hipper. After all, they were your curls and you’ve done what you thought best.”

Mary later claimed she “wasn’t at all prepared for was the avalanche of criticism that overwhelmed me from all corners of the earth. You would have thought I had murdered someone, and perhaps I had, but only to give her successor a chance to live.” Laurence Irving described her fans’ surprise by saying, “If the Pope had appeared in St. Peter’s with a full-bottomed wig, his global flock would have been no less shocked.”

Mary later claimed she “wasn’t at all prepared for was the avalanche of criticism that overwhelmed me from all corners of the earth. You would have thought I had murdered someone, and perhaps I had, but only to give her successor a chance to live.” Laurence Irving described her fans’ surprise by saying, “If the Pope had appeared in St. Peter’s with a full-bottomed wig, his global flock would have been no less shocked.”

Movie magazines couldn’t write enough about the haircut and Mary was quoted often, mostly in apologetic tones. But she also pointed out, “Wouldn’t you think it a very sad business indeed for an actress to be made to feel that her success depended solely, or at least in large part, on a head of hair.”

Ironically, her hair might have been much shorter, but for the first time in her life she had to start going to the hairdresser regularly. “I naturally missed the curls, after they were gone… For weeks I told myself that I shouldn’t have done it. I thought it would free me. That was what I had been hoping and I suppose in a way it did, because I began to feel a change, in me personally, a sense of ease and liberation I hadn’t known before. “

She said her hair cut was “my final revolt against the type of thing I had been doing. There was no retracing my steps now. I made Coquette and had the great satisfaction of winning the Academy Award. For that my curls had been a very small price to pay.”