Carl Laemmle’s decision in early 1911 to send most of IMP’s company to Cuba seemed like such a good idea. It put plenty of miles and even some water between them and the Trust and they could take advantage of Cuba’s warm climate, tropical locations and cheap local labor. Yet from the beginning, the excursion was ill-fated.

Carl Laemmle’s decision in early 1911 to send most of IMP’s company to Cuba seemed like such a good idea. It put plenty of miles and even some water between them and the Trust and they could take advantage of Cuba’s warm climate, tropical locations and cheap local labor. Yet from the beginning, the excursion was ill-fated.

Professionally, the pressure was on Mary Pickford as never before because she was the one “star” in the group. Her supporting cast consisted of a ragtag band, such as one young man in amateur looking make-up masquerading as her father and a technician who was plucked from the laboratory to play her love interest in The Toss of a Coin.

Ever since Mary had revealed she was married to Owen Moore, she found herself pulled between trying to soothe relations with her estranged family and assuring her husband that all would be well. Her mother didn’t make things any easier. When they arrived at their lodgings, Charlotte pointed to one bedroom and announced with authority, “You take that room, Owen. Mary and I will sleep in here.” As Mary put it, “I soon discovered that Owen was jealous, not of the other men in the company, but of my family and my family of course returned the compliment with interest.”

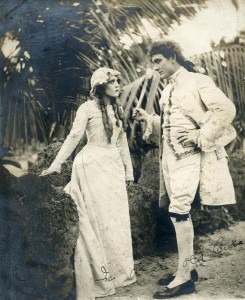

Thomas Ince, who would become a major film producer, was her director, but he was a novice at the time. His learning curve was not helped by the fact that all the film was sent back to New York to be developed. Ince, along with everyone else in the company, could not watch dailies to see what their movie looked like, but Mary didn’t need film to know that the humid Cuban weather played havoc with her longs curls which now required new constant tending when the cameras weren’t rolling. To hide his inexperience, Ince became overly dependent on locations and his films were heavily laced with shots of the harbor, tobacco fields and palm trees.

Mary claimed that their time in Cuba mercifully ended earlier than planned when Owen got into a fistfight with Ince’s assistant and the police were called. Charlotte stepped in and argued with the authorities long enough for Owen to slip on board a ship. “The next morning at dawn, I joined Owen on the boat in Havana Harbor and sailed back to the United States.”

Mary claimed that their time in Cuba mercifully ended earlier than planned when Owen got into a fistfight with Ince’s assistant and the police were called. Charlotte stepped in and argued with the authorities long enough for Owen to slip on board a ship. “The next morning at dawn, I joined Owen on the boat in Havana Harbor and sailed back to the United States.”

The rest of the Pickfords returned shortly thereafter and Mary and Owen continued to work together at IMP for several more months. They had their own apartment for awhile, but Mary had no experience in real life relationships outside of her immediate family and, being raised on trains and in boardinghouses, knew even less about domestic skills. And her mother was always there; in their home, at the studio and even traveling with them. Mary’s star was rising and Owen’s, if not descending, was standing still and his drinking did not help matters. All these factors, combined with different shooting schedules, made for a troubled marriage.

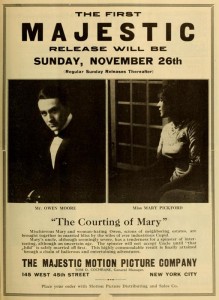

While Carl Laemmle was off in Europe in the fall of 1911, Harry Aitken, an entrepreneurial distributor, formed the Majestic Motion Picture Company and staffed it, in large part, by raiding IMP. Amongst others, Aitken brought over Thomas Cochrane to be his general manager and Mary Pickford to be his star. (He accomplished this by raising her salary to $225 a week and agreeing to sign Owen as well.) Where the Trust forbade fellow companies from stealing their talent, the Independents only had the courts to fall back on so Laemmle sued Mary for breaking her contract with him. She took the stand and testified it was Laemmle who had broken his contracts, not only with Lottie and Jack, but with her as well because she had been forced to endure an “affront to her art” through compromises such as “co-stars” who were really lab men and other unprofessional indignities. Never mind that movies were hardly considered art in 1911; she read from newspaper reviews to establish her stardom and talent. In the end, the court voided her contract because she had been a minor when she signed it. But once again, we see how seriously she took her work and how she did not shirk from standing up for herself.

While Carl Laemmle was off in Europe in the fall of 1911, Harry Aitken, an entrepreneurial distributor, formed the Majestic Motion Picture Company and staffed it, in large part, by raiding IMP. Amongst others, Aitken brought over Thomas Cochrane to be his general manager and Mary Pickford to be his star. (He accomplished this by raising her salary to $225 a week and agreeing to sign Owen as well.) Where the Trust forbade fellow companies from stealing their talent, the Independents only had the courts to fall back on so Laemmle sued Mary for breaking her contract with him. She took the stand and testified it was Laemmle who had broken his contracts, not only with Lottie and Jack, but with her as well because she had been forced to endure an “affront to her art” through compromises such as “co-stars” who were really lab men and other unprofessional indignities. Never mind that movies were hardly considered art in 1911; she read from newspaper reviews to establish her stardom and talent. In the end, the court voided her contract because she had been a minor when she signed it. But once again, we see how seriously she took her work and how she did not shirk from standing up for herself.

Even though the name of Mary Pickford now appeared in the press, she was commonly referred to as “The Girl with the Curls” and “Little Mary,” in part because that was the name her characters were often given. To play that up, her first Majestic film was entitled The Courting of Mary. Her agreement with Majestic included the provision that Owen not only come with her, but be given the opportunity to direct. Mary claimed that Owen never knew that her contracts mandated that he be retained as well, but said that he had “deeply resented that I made more money than he did.” It was one thing for a child to be the breadwinner for the Pickford family, but it was a constant source of strain for the Moores.

Mary hoped that if Owen was promoted to being a director, his confidence would return and their relationship would have a chance. But in his new power position, Owen put her down in front of others, verbally attacking her as a person and as an actress. He directed her in Little Red Riding Hood and a picture of Mary in costume for that film was featured in the first issue of Photoplay, a pioneer in what would soon become the fan magazine industry. She looks none too happy in the photograph, but other pictures taken of her with Owen at the time show that she clearly adored him and was trying to make things work.

Mary hoped that if Owen was promoted to being a director, his confidence would return and their relationship would have a chance. But in his new power position, Owen put her down in front of others, verbally attacking her as a person and as an actress. He directed her in Little Red Riding Hood and a picture of Mary in costume for that film was featured in the first issue of Photoplay, a pioneer in what would soon become the fan magazine industry. She looks none too happy in the photograph, but other pictures taken of her with Owen at the time show that she clearly adored him and was trying to make things work.

Still, little was going as Mary had hoped and so she reached out for the one thing over which she felt she could exert some control: the quality of her films. In January of 1912, she returned to Griffith and Biograph while Owen went to work for yet another independent company. It would be the only time she took a step backward in salary – down to $175 a week – but it seemed a small price to pay to be a part of a community where she felt supported.