It’s almost a misnomer to entitle an article “Mary Pickford’s Childhood,” because in many ways, she didn’t have one. Mary Pickford rose steadily to fame at a time when there was no path to follow. Actresses who came after her dreamed of stardom, but Mary Pickford’s first dreams, from the age of six on, were of supporting her family. As she later explained her reason for going on the stage and then before the cameras, “It was a matter of economics.”

It’s almost a misnomer to entitle an article “Mary Pickford’s Childhood,” because in many ways, she didn’t have one. Mary Pickford rose steadily to fame at a time when there was no path to follow. Actresses who came after her dreamed of stardom, but Mary Pickford’s first dreams, from the age of six on, were of supporting her family. As she later explained her reason for going on the stage and then before the cameras, “It was a matter of economics.”

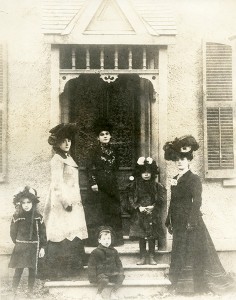

Pickford was born Gladys Louise Smith on April 8, 1892 in Toronto, Canada to John and Charlotte Smith. Her sister Charlotte, always called Lottie, was born the following year and a younger brother, John Charles Jr, dubbed Jack, arrived in 1896. Around the time of Jack’s birth, Gladys’ father left his family and within a year and a half, died after suffering an accident at work. What money the Smiths had went to pay medical bills and even though she had three children to care for, Charlotte became “paralyzed” with grief, according to an interview Mary gave later in life. It was only when little Jack became deathly ill five months after John’s passing that Charlotte snapped out of her self-imposed isolation and went back to the business of tending her family. Charlotte took in sewing and rented out the master bedroom of their University Avenue home to survive, and one of the first boarders was a stage manager for a theatrical stock company. He offered to put little Gladys and her sister Lottie on the stage and, after Charlotte assured herself of the gentility of the company, Gladys’ theatrical debut in The Silver King featured her as a young girl with one line and then a boy playing with toys.

At first, Gladys’s mother, sister and brother traveled with her, each playing roles in various stock companies whenever they could get cast. But Gladys was the one producers wanted and soon she was traveling alone throughout Canada and to New York for work.

She had only a few months of structured schooling at best and taught herself to read on those train rides, burying her head in books so she could learn but also to avoid contact with strangers. “By the time Gladys was twelve,” writes Pickford biographer Booton Herndon, “she knew how to travel better than most adults, certainly better than most women of 1905. She knew how to get around in a town she had never seen before, how to get a room at a reasonable price, how to eat cheaply, when to walk rather that spend a nickel for a streetcar.” She was not above sleeping in an overstuffed chair and paying “rent” by doing the shopping and cleaning, saving every penny she could to proudly send home to her mother at the end of each week.

She had only a few months of structured schooling at best and taught herself to read on those train rides, burying her head in books so she could learn but also to avoid contact with strangers. “By the time Gladys was twelve,” writes Pickford biographer Booton Herndon, “she knew how to travel better than most adults, certainly better than most women of 1905. She knew how to get around in a town she had never seen before, how to get a room at a reasonable price, how to eat cheaply, when to walk rather that spend a nickel for a streetcar.” She was not above sleeping in an overstuffed chair and paying “rent” by doing the shopping and cleaning, saving every penny she could to proudly send home to her mother at the end of each week.

Gladys had just turned fifteen in the summer of 1907 when she bombarded the preeminent Broadway producer David Belasco with letters and photographs of herself, eventually winning the role of young Betty in his production of The Warrens of Virginia, written by William de Mille and co-starring his younger brother Cecil.

It was Belasco who decided that Gladys Smith needed a new name and together they reviewed her family tree for one with marquee value. They stopped at her maternal grandfather Jack Pickford Hennessey and she proudly wired her mother, “Gladys Smith now Mary Pickford engaged by David Belasco to appear on Broadway this fall.” As if to underscore their dedication to her future, the rest of the family adopted the name Pickford as well. Yet even before she became Mary Pickford, Gladys Smith had accepted the role of provider and all the responsibilities that went with it.

When she was a star and being interviewed, Mary usually became stoic about her years in stock companies and on the stage, putting a smiling face on her past. But to her friend Frances Marion she broke down in tears, telling her, “I was the most miserable kid in the world.” Once Mary and Jack got to talking about their younger years and it suddenly occurred to him what she had gone through. “Poor kid, you never had a childhood, did you?” When Lottie was asked about their childhood, she responded “We had none.” But then with the touch of resentment that always tinged their relationship, she added, “Mary has always been ‘Little Mother’ to the whole family. She was constantly looking after our needs. I always used to think that she imagined Jack and I were just her big dolls.” Jack would prove himself a talented actor, but his hankering for a good time usually proved stronger than his desire to work and Lottie stopped working even intermittently, secure in the knowledge that Mary was there to bankroll her lifestyle.

Mary and her mother were extraordinarily close, almost more like sisters than mother and daughter. Once Mary’s work appeared secure, the family permanently reunited in New York. And it was there in April of 1909, after The Warrens of Virginia had closed and Broadway theaters were about to shut down for the summer, that Mary swallowed her pride and knocked on the door of a former mansion on East 14th Street where the Biograph company was making movies in what used to be the ballroom. That day she met the frustrated actor turned director, D.W. Griffith, and her truly adult life was about to begin.