Margaret Case Harriman on Mary Pickford

Margaret Case Harriman was a talented, droll and understated observer of people. She may have come by those skills naturally as she was the daughter of Frank Case, owner of the Algonquin Hotel on New York’s West 44th St. Born in 1904 in room 1206 of the Algonquin, Margaret said she “practically grew up with her chin on the table,” and so used to being among the famous “that I came to take them with a great and perhaps regrettable calm.” When Alexander Woollcott began bringing his friends there for lunch in 1919 – both Vanity Fair and then The New Yorker offices were in the neighborhood – Margaret’s father reserved a round table for them daily, and a tradition was born. Margaret was married twice – once to a Morgan and once to a Harriman – but she found quiet fame and respect as a profile writer for Vanity Fair and The New Yorker. She was also the author of several books, including The Vicious Circle, heralded as one of the best on the famed Round Table.

Margaret Case Harriman was a talented, droll and understated observer of people. She may have come by those skills naturally as she was the daughter of Frank Case, owner of the Algonquin Hotel on New York’s West 44th St. Born in 1904 in room 1206 of the Algonquin, Margaret said she “practically grew up with her chin on the table,” and so used to being among the famous “that I came to take them with a great and perhaps regrettable calm.” When Alexander Woollcott began bringing his friends there for lunch in 1919 – both Vanity Fair and then The New Yorker offices were in the neighborhood – Margaret’s father reserved a round table for them daily, and a tradition was born. Margaret was married twice – once to a Morgan and once to a Harriman – but she found quiet fame and respect as a profile writer for Vanity Fair and The New Yorker. She was also the author of several books, including The Vicious Circle, heralded as one of the best on the famed Round Table.

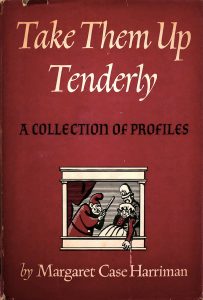

Margaret was still a preteen when she first met Mary Pickford as Frank Case was one of Doug Fairbanks’ best friends. Doug, of course, often stayed at the Algonquin and Frank made several cross-country trips to visit them at Pickfair. It is interesting to read a female observer’s take on Mary, and while Margaret doesn’t hold back with her opinions, she clearly has a deep respect for the actress. The excerpted version below is from a profile originally written for The New Yorker, reprinted in one of Harriman’s delightful collections, Take Them Up Tenderly.

“It was no accident of golden curls that made Mary the richest and most famous movie-picture star in the world. America’s sweetheart is a businesswoman, hardheaded, patient, and positive. The conferences that, in 1919, proceeded the forming of United Artists – meetings that included Chaplin, Fairbanks, D.W. Griffith, and their lawyers – were quietly dominated by Mary. She had then, as she has now, the gift of intelligent listening, but at the end of one of these thoughtful silences, her rather high, Canadian voice would announce, “I disagree with you, gentlemen, and I will tell you why.” It generally turned out that she was right. The United Artists Corporation was her idea, to start with. Earlier, in 1918, when she was an independent producer, she had released her pictures through First National, but had found this method of distributing her product to be unsatisfactory. Through the system of “block booking” (Selling to an exhibitor the picture he wants only if he will buy a certain number of other pictures along with it), First National was making Mary’s pictures support a whole train of mediocre productions, and she saw that this was highly uneconomic for her. It occurred to her that she could make much better profits by organizing a deluxe company to release the pictures of only the biggest stars. United Artists was the result.

“It was no accident of golden curls that made Mary the richest and most famous movie-picture star in the world. America’s sweetheart is a businesswoman, hardheaded, patient, and positive. The conferences that, in 1919, proceeded the forming of United Artists – meetings that included Chaplin, Fairbanks, D.W. Griffith, and their lawyers – were quietly dominated by Mary. She had then, as she has now, the gift of intelligent listening, but at the end of one of these thoughtful silences, her rather high, Canadian voice would announce, “I disagree with you, gentlemen, and I will tell you why.” It generally turned out that she was right. The United Artists Corporation was her idea, to start with. Earlier, in 1918, when she was an independent producer, she had released her pictures through First National, but had found this method of distributing her product to be unsatisfactory. Through the system of “block booking” (Selling to an exhibitor the picture he wants only if he will buy a certain number of other pictures along with it), First National was making Mary’s pictures support a whole train of mediocre productions, and she saw that this was highly uneconomic for her. It occurred to her that she could make much better profits by organizing a deluxe company to release the pictures of only the biggest stars. United Artists was the result.

She has always had a pretty alert idea of what the public wants. Not long after her marriage to Douglas Fairbanks, in 1920, the Victor Talking Machine Company offered them twenty thousand dollars to make a talking record together. Douglas thought it might be a good idea; Mary disagreed. ‘I know’, she said, ‘what a phonograph record can be like, once you get sick of it. People follow us in the street now, and mob us at theaters, but if they have that phonograph record at home, and children, maybe, who like to play it over and over, they might get sick of the whole thing, and of us, too.’

***

The biographical facts about Mary Pickford are already familiar to the public. She was born in Toronto, and her name was Gladys Smith; her father, an impractical Englishman, died when she was four, and in 1899, at the age of six, Mary went to work for the Valentine Stock Company in Toronto. The careers of Lottie and Jack were from the beginning nebulous and uncertain, but Mary had inherited her Irish mother’s persistency – that quality which had enabled Charlotte Smith to find work for her children, and an occasional acting job for herself, until Mary was launched as the breadwinner of the family. When she was fourteen, Mary made her first film for Biograph; it was directed by D.W. Griffith and called Her First Biscuits. After that, she began to be known as “the Biograph girl,” and her pay in one year and a half was raised from $40 a week to $5000 a year, a lavish motion-picture salary for those days. After a stage appearance under the direction of David Belasco in A Good Little Devil, she made, in 1913, a movie of the play for Famous Players. Two years later she became vice-president of the Mary Pickford-Famous Players Company at a salary of $2000 a week and fifty percent of the profits, and when, in the following year, her own company was organized under the name of Artcraft Pictures, Mary salary was more than doubled, and she still received her share of the profits. She became an independent producer in 1918, one year before the organization of United Artists, releasing a series of pictures – notably Daddy Long Legs – through First National. In the handling of her present fortune, estimated at between two and four million, Mary is practical and shrewd, but money in the form of a twenty dollar bill or a check for ten times that amount means little to her. When she was ten years old, she played in Chicago in a melodrama called The Child-Wife; her salary then was $30 a week, and she did her own laundry in the basement of her boarding house. Thirty years later, in 1934, she made her second stage appearance in that city, for a week, for which she got $15,000.

The biographical facts about Mary Pickford are already familiar to the public. She was born in Toronto, and her name was Gladys Smith; her father, an impractical Englishman, died when she was four, and in 1899, at the age of six, Mary went to work for the Valentine Stock Company in Toronto. The careers of Lottie and Jack were from the beginning nebulous and uncertain, but Mary had inherited her Irish mother’s persistency – that quality which had enabled Charlotte Smith to find work for her children, and an occasional acting job for herself, until Mary was launched as the breadwinner of the family. When she was fourteen, Mary made her first film for Biograph; it was directed by D.W. Griffith and called Her First Biscuits. After that, she began to be known as “the Biograph girl,” and her pay in one year and a half was raised from $40 a week to $5000 a year, a lavish motion-picture salary for those days. After a stage appearance under the direction of David Belasco in A Good Little Devil, she made, in 1913, a movie of the play for Famous Players. Two years later she became vice-president of the Mary Pickford-Famous Players Company at a salary of $2000 a week and fifty percent of the profits, and when, in the following year, her own company was organized under the name of Artcraft Pictures, Mary salary was more than doubled, and she still received her share of the profits. She became an independent producer in 1918, one year before the organization of United Artists, releasing a series of pictures – notably Daddy Long Legs – through First National. In the handling of her present fortune, estimated at between two and four million, Mary is practical and shrewd, but money in the form of a twenty dollar bill or a check for ten times that amount means little to her. When she was ten years old, she played in Chicago in a melodrama called The Child-Wife; her salary then was $30 a week, and she did her own laundry in the basement of her boarding house. Thirty years later, in 1934, she made her second stage appearance in that city, for a week, for which she got $15,000.

***

Through it all – the failure of her marriage to Owen Moore, the loss of her mother and her brother, and her separation and divorce from Douglas – she was sustained less by her optimism than by her passion for work. For months before her stage appearance in a one-act vaudeville sketch several years ago she had four lessons a day in singing and speaking, to develop her voice, which, although improved by talking pictures, still retained a good deal of its natural, slightly breathless tone. It cannot, even now, be called mellow, but its strength and flexibility have increased, and her enunciation is excellent. She took piano lessons at the same time, and would stay for hours in an upper room at Pickfair, practicing breathing exercises, scales, recitations, and songs. The windows of that room, over the servants’ entrance, were kept closed because Mary was nervous about having the delivery boys hear her. She did laughing exercises, too, and is apt to do them now when she has a few minutes to spare, beginning with a careful laugh on a low note and ending in a rich peal; it sounds fairly eerie in her suite at the Sherry-Netherland. She likes to try to give as much as possible of a long speech from any play in one breath, and to recite The Raven, with expression; her teacher has been scrupulous about the different inflections of “nevermore.” Her singing voice, low at first, is getting higher, and she can reach high C now, but it upsets her to have to do it. The first song she learned was “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?” followed by “Gather Lip-Rouge While You May,” “My Wild Irish Rose” and the Leland Stanford college song “Hail, Stanford, Hail!” Her biggest number is the “Parlez-moi d’amour,” which she sings and plays with considerable dreaminess. At one time she had a French teacher on the set with her every day, and took lessons between camera shots until she had learned to speak the language, as she does today, with a successful lack of accent and affair fluency. She wants some day, to active play in French, possibly Musset’s Il fait qu’une porte soit ouverte ou fermee.

***

She is scrupulous about her appearance in public, because she feels that people expect her to look well. The first time she was recognized on a New York street (it was in front of the Strand Theater in 1914), she had on an ugly hat, and it worried her for days – not to such an extent, however, that she forgot to ask for a raise on the strength of the public recognition. At home, she has no personal vanity at all, and will sit talking for hours with a shiny nose and her hair done up in pins or pulled straight back from her face – a style that, quite by accident, is very becoming. Her hair is about 3 inches long in back and naturally wavy; she has a vegetable rinse with every third or fourth shampoo to keep the lights in it. She weighs, now, one hundred and two pounds, and is exactly five feet tall. Her size, in her own opinion, is one reason public officials like to be photographed with her; it makes them look bigger.

Three months schooling in Toronto at the age of five was the extent of Mary’s formal education, but much of her spare time since has been devoted to learning. Her reading is disciplinary rather than intellectual. When she can, she reads a little, slowly, of a book she has heard about, sometimes taking 20 minutes to a page, because she stops to memorize in order to increase her facility for learning parts. When she lives in a hotel, there are no books and no other evidences of personality to be found about her rooms, except Science and Health and one or two current biographies.

She is never idol and never rests during the day. Even when she is playing four shows daily in personal appearances at picture houses, she never lies down until she goes to bed for the night. She is almost never alone; her remaining relatives – Gwynne Pickford, her niece; Verna Chalif, a cousin; and her two adopted children, Ronnie and Roxanne – generally surround her, as well as the usual retinue of a movie personage: two secretaries, two maids, managers, and lawyers. Sometimes, faced with a problem, Mary goes into her bedroom alone and talks out loud to herself. These private monologues are apt to sound very fierce, and Mary emerges from them pale but positive.

United Artists is now controlled by Mary, David Selznick, Sir Alexander Korda, and Chaplin. When Mary bought Junior Miss for pictures last winter, she sat in conference over certain technical points of the deal with 10 men, some of whom had not met her before. They were Fleischer, the negotiator, Cohen, his assistant, Rafferty and O’Brien of O’Brien, Malevinsky & Driscoll (Mary’s lawyers), Grad Sears, distribution head of United Artists, Sol Myers, attorney for the authors, Max Gordon, A. L. Behrman, his attorney, Paul Streger of the Leland Hayward office (agents for the authors), and Howard Reinheimer, Hayward’s lawyer. ‘It took us 10 guys about five minutes to catch on to just who was going to be the focal point of that meeting, whose business head was going to prevail,’ Streger said afterward, shaking his head admiringly. ‘Little Mary was it, all right.’ Mary bought Junior Miss for $355,000 plus thirty-five percent of the profits.”

United Artists is now controlled by Mary, David Selznick, Sir Alexander Korda, and Chaplin. When Mary bought Junior Miss for pictures last winter, she sat in conference over certain technical points of the deal with 10 men, some of whom had not met her before. They were Fleischer, the negotiator, Cohen, his assistant, Rafferty and O’Brien of O’Brien, Malevinsky & Driscoll (Mary’s lawyers), Grad Sears, distribution head of United Artists, Sol Myers, attorney for the authors, Max Gordon, A. L. Behrman, his attorney, Paul Streger of the Leland Hayward office (agents for the authors), and Howard Reinheimer, Hayward’s lawyer. ‘It took us 10 guys about five minutes to catch on to just who was going to be the focal point of that meeting, whose business head was going to prevail,’ Streger said afterward, shaking his head admiringly. ‘Little Mary was it, all right.’ Mary bought Junior Miss for $355,000 plus thirty-five percent of the profits.”

Excerpted from Take Them Up Tenderly: A Collection of Profiles, by Margaret Case Harriman, New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1944

Pgs 243-251

— Cari Beauchamp