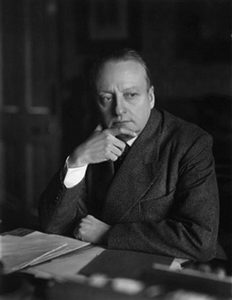

Edward Knoblock on Rosita

Edward Knoblock first entered the world of Pickford and Fairbanks when Doug hired him to help script The Three Musketeers in 1921. Knoblock was a prolific playwright and novelist best known for his 1911 play, Kismet. Doug sought out the best talent he could find, but he also assumed that once they signed up, they would happily join in the male camaraderie his studio was famous for. The American born, British citizen Knoblock was Harvard educated and in his mid-forties, too mature and accomplished to be amused by being a part of an entourage. As Knoblock put it in his memoir, “I was given a most dignified office, paneled with mahogany and here I waited daily for Douglas to decide…”

Edward Knoblock first entered the world of Pickford and Fairbanks when Doug hired him to help script The Three Musketeers in 1921. Knoblock was a prolific playwright and novelist best known for his 1911 play, Kismet. Doug sought out the best talent he could find, but he also assumed that once they signed up, they would happily join in the male camaraderie his studio was famous for. The American born, British citizen Knoblock was Harvard educated and in his mid-forties, too mature and accomplished to be amused by being a part of an entourage. As Knoblock put it in his memoir, “I was given a most dignified office, paneled with mahogany and here I waited daily for Douglas to decide…”

However, Knoblock did enjoy Mary and Doug as friends and admired them as artists so he was pleased to cross the Pickford Fairbanks Studio lot to write Rosita. His observations from the set provide a unique look at the relationship between Lubitsch and Pickford and confirm that Mary wasn’t the only one who had “issues” with the director. And Knoblock’s memory of Lubitsch admitting how “terrified” he was directing the film, explains a lot.

“Meanwhile I filled in my time by writing a film for Mary Pickford. She felt it might be wise for her to act the part of a young girl whose experiences, as the story progressed, made her grow up to womanhood. In this way she hoped to bridge her career to maturer parts. For she was tired of forever playing a little girl in her early ‘teens. And she thought the public must be growing tired of it, too. But she was mistaken. For though she gave an exquisite performance in Rosita, her ‘fans’ were disappointed to see their curly-headed idol put up her tresses and appear in a role so different from what they were used to. The film was not a failure; but it was also not an outstanding success. And this I set down a good bit to the continued publicity of her press-agent, who had for years drummed it into the public’s mind that Mary was a dear little baby-girl.

“Meanwhile I filled in my time by writing a film for Mary Pickford. She felt it might be wise for her to act the part of a young girl whose experiences, as the story progressed, made her grow up to womanhood. In this way she hoped to bridge her career to maturer parts. For she was tired of forever playing a little girl in her early ‘teens. And she thought the public must be growing tired of it, too. But she was mistaken. For though she gave an exquisite performance in Rosita, her ‘fans’ were disappointed to see their curly-headed idol put up her tresses and appear in a role so different from what they were used to. The film was not a failure; but it was also not an outstanding success. And this I set down a good bit to the continued publicity of her press-agent, who had for years drummed it into the public’s mind that Mary was a dear little baby-girl.

This brings me to the subject of publicity and the great danger it can prove to film-stars. They ultimately end by becoming slaves to it, branded by the burning-iron to which they have willingly submitted themselves. They are permanently labeled as this or that and if they attempt to alter the label their public is bewildered and resents the change….

Mary Pickford had sent for Ernst Lubitsch to come over from Germany in order to direct Rosita. She had admired his work and felt that it would be advantageous of her to find a fresh inspiration under the guidance of a new director.

Ernst Lubitsch arrived – a keen-eyed, very intelligent, energetic, pudgy man. He had tried to learn English on his way to California. The result was at times extremely comic. One day he kept running about the studio shouting:

Ernst Lubitsch arrived – a keen-eyed, very intelligent, energetic, pudgy man. He had tried to learn English on his way to California. The result was at times extremely comic. One day he kept running about the studio shouting:

‘Vere iss dem dajer mid vat he iss geshtickt?’

It took some time before I realize that he was trying to say:

‘Where is the dagger that he is stabbed with?’

Another time, when he and I had a difference about the treatment of a scene, he lost his temper and started rushing off the set, but turned a second to face me and by way of an annihilating farewell exclaimed: ‘How do you do,’ which produced an Homeric guffaw throughout the studio, including the electricians on their perches. Years later, when we met again in London, I found he spoke a most fluent vernacular of rich Californian, embellished with all the raciness of American slang. I recalled his early linguistic efforts to him. He laughed most heartily – for no one has a keener sense of humor than Lubitsch. He confessed to me then that during that first venture of his in Hollywood, he had been frankly terrified.”

From Around the Room by Edward Knoblock, London, Chapman and Hall, 1939.

– Cari Beauchamp