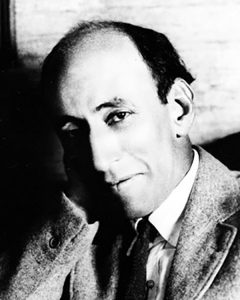

William DeMille on Mary Pickford

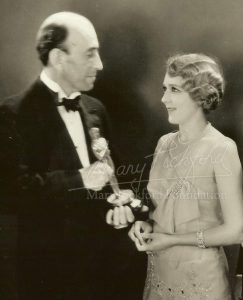

William deMille followed his younger brother Cecil to Hollywood in 1914 and worked as a screenwriter, a director and a producer primarily for Famous Players Lasky/Paramount. William didn’t know Mary as well as his brother did, but he was in a position to observe her at relatively close range over a number of decades. She had first come into William’s orbit when she appeared on Broadway in his play, “The Warrens of Virginia” in 1907. In his autobiography, Hollywood Saga, William wrote about Mary with his tongue firmly implanted in his cheek as the following except attests:

William deMille followed his younger brother Cecil to Hollywood in 1914 and worked as a screenwriter, a director and a producer primarily for Famous Players Lasky/Paramount. William didn’t know Mary as well as his brother did, but he was in a position to observe her at relatively close range over a number of decades. She had first come into William’s orbit when she appeared on Broadway in his play, “The Warrens of Virginia” in 1907. In his autobiography, Hollywood Saga, William wrote about Mary with his tongue firmly implanted in his cheek as the following except attests:

Mary, of course, was the ideal picture star. In addition to having beauty which appealed to all ages, sexes and races, she had a camera-proof face; it was impossible to find an angle from which she looked unattractive. After eighteen years of professional experience she was twenty-two years old. Her mother had been left a widow with three small children to support, Lottie, Mary and Jack, and, refusing to be separated from the youngsters, had taken them along when she acted in traveling road shows and small stock companies. Jack, the baby, had slept in a wardrobe trunk in Mother Pickford’s dressing room, attended by his slightly older sisters. They had learned their theater the hard way, and Mary had been on the stage from the time she could walk. She had been one of the first to see the screen’s future possibilities and had been fortunate in getting her early picture training from D.W. Griffith, who was undoubtedly the first master-director in the United States. She was, and still is, an indefatigable worker, and her early success was no accident.

God gave her beauty, it is true, but God apparently also created many beautiful dumb-bells. A large number of these have, from time to time, been offered to the picture public as potential favorites, but none of them had the energy, the courage, the personality and the intelligence of Mary Pickford. For more than twenty years she held her following, while other beauties were being raised up and cast down with heart-breaking rapidity. Even when Mary turned to producing instead of acting, she was still “America’s Sweetheart”; a crowd still waits wherever it is known she will be; maids in hotels and waiters in restaurants still feel their hearts miss a few beats when they have opportunity to serve her, just as they felt twenty years ago. That this little lady was also an extremely shrewd businesswoman, and at no time underestimated her market value, was another element which did nothing to detract from her material success….

God gave her beauty, it is true, but God apparently also created many beautiful dumb-bells. A large number of these have, from time to time, been offered to the picture public as potential favorites, but none of them had the energy, the courage, the personality and the intelligence of Mary Pickford. For more than twenty years she held her following, while other beauties were being raised up and cast down with heart-breaking rapidity. Even when Mary turned to producing instead of acting, she was still “America’s Sweetheart”; a crowd still waits wherever it is known she will be; maids in hotels and waiters in restaurants still feel their hearts miss a few beats when they have opportunity to serve her, just as they felt twenty years ago. That this little lady was also an extremely shrewd businesswoman, and at no time underestimated her market value, was another element which did nothing to detract from her material success….

Although always a sincere artist in her work, Mary was also a student of the Bible and believed that the laborer was worthy of his hire. This she gently explained to Mr. Zukor, telling him that she hadn’t the slightest intention of being unreasonable but that she just couldn’t see her way clear to work for less than seven thousand large, round, gold-standard dollars per week plushalf the profits of her pictures. Mr. Zukor couldn’t possibly afford to let Mary go at that time; her pictures were a powerful aid in selling the whole Paramount program, so a deal was made and Mary began to drop quite a few nickels into her little savings bank.

But by 1918 things had come to a point where the patient Mr. Zukor was beginning to wonder if, after all, he could afford to keep Mary working for him, or if he wouldn’t save a lot of money by simply giving her the studio and taking a small salary for himself.

But by 1918 things had come to a point where the patient Mr. Zukor was beginning to wonder if, after all, he could afford to keep Mary working for him, or if he wouldn’t save a lot of money by simply giving her the studio and taking a small salary for himself.

First National, a new and striving competitor, had just offered America’s Sweetheart $225,000 each, for three pictures a year. They needed her name on their program and figured it was worth that sum to get her away from Paramount and into their own camp.

Seeing no way of successfully grasping this bull by the horns, the adroit Mr. Zukor tried to lead it gently by the nose. With compassionate eye and throbbing voice he told Mary that she was tired, that she had been working much too hard for many years and needed a long rest. No line must ever be allowed to mar her beautiful face, nor should that face ever appear on any screen save Paramount’s. Just think what Mary and Paramount had meant to each other these last few years! The thought of her going to another company, where perhaps she would not be so well loved, hurt the kindly Mr. Zukor in his deepest and most sensitive feelings. So, just for friendship and auld lang syne, he would give her one thousand dollars every week for five years on condition that she would take a complete rest during that period and not bother her pretty little head about pictures at all.

Mary’s large, soulful and expressive eyes opened wide as she regarded her generous benefactor with feeling. She was much touched and deeply moved. If the thought occurred to her that, from Paramount’s point of view, it was well worth $260,000 to eliminate her for five years as a competitor she brushed it aside as unworthy. She, too, knew what friendship meant, and her affection for dear, considerate Mr. Zukor was fully as deep as his for her. But, after all, she was only a young girl just on the threshold of what might prove to be a successful career. She was a little tired, perhaps, but not quite tired enough to take a five years’ vacation, at the end of which she would undoubtedly be five years older. So, while she knew that Mr. Zukor, old and trusted friend as he was, had only her best interest in mind, she felt that she owed something to her art as well as to her public which, in a few short years, had set such a price on her services that Mr. Zukor, anticipating the economic principles of a later generation, was willing to pay her a thousand dollars a week for not making pictures; fifty-two thousand a year to let herself be plowed under.

Mary’s large, soulful and expressive eyes opened wide as she regarded her generous benefactor with feeling. She was much touched and deeply moved. If the thought occurred to her that, from Paramount’s point of view, it was well worth $260,000 to eliminate her for five years as a competitor she brushed it aside as unworthy. She, too, knew what friendship meant, and her affection for dear, considerate Mr. Zukor was fully as deep as his for her. But, after all, she was only a young girl just on the threshold of what might prove to be a successful career. She was a little tired, perhaps, but not quite tired enough to take a five years’ vacation, at the end of which she would undoubtedly be five years older. So, while she knew that Mr. Zukor, old and trusted friend as he was, had only her best interest in mind, she felt that she owed something to her art as well as to her public which, in a few short years, had set such a price on her services that Mr. Zukor, anticipating the economic principles of a later generation, was willing to pay her a thousand dollars a week for not making pictures; fifty-two thousand a year to let herself be plowed under.

Timidly, in her innocent, childlike way, she explained all this to the man who was so anxious to protect her from the hard life of professional exertion. Tempting as his offer was, she would rather work for $675,000 per annum than rest for $52,000. She had certain obligations, and that difference of $623,000 every year would go a long way toward helping her to meet them. It desolated her to think of leaving Paramount where she had been so happy and contented, but, after all, duty was a much nobler goal than mere happiness; so unless Mr. Zukor could see his way clear to meet these terms – The poor child could say no more; she was a young artist, and they kept forcing her to talk about money.

While overly flowery and word play abounds, deMille’s account is interesting for many reasons. It is unique in that it is one of the few on Mary’s early years that does not even mention her mother Charlotte. Charlotte of course is often credited with being the brains behind the contract negotiations as well as being the bad cop that allowed Mary to appear unconcerned about finances. Perhaps deMille had become a true producer by the time he wrote this in — because he fails to mention block booking and the fact Mary knew it was her films (as well as Doug’s) that were selling the dozens of other Paramount films exhibitors had to buy to get those starring Pickford and Fairbanks. Just the same, it is a variation on the story of how she went (briefly) to First National before forming United Artists and makes for an intriguing version of events, particularly when compared to others of the era.

(William deMille kept the family’s traditional spelling of their last name while C.B. chose to capitalize the D).

– Cari Beauchamp

Sources

From Hollywood Saga by William C. DeMille, E.P. Dutton & Co., New York 1959

Pages 146-147; 233-236