Newspapers were the primary means of communication in the 1910s. New York alone had twenty daily papers – there were morning papers, afternoon papers and evening papers with extra editions when scandals or big news broke. Competition was stiff and one of the ideas that emerged to set local papers apart was syndicated columns – paying big money to celebrities and selling their stories to just one newspaper in each of hundreds of cities and towns for simultaneous publication. Syndication offered newspapers a way to stand out in the crowd for little investment – if the draw was right.

Newspapers were the primary means of communication in the 1910s. New York alone had twenty daily papers – there were morning papers, afternoon papers and evening papers with extra editions when scandals or big news broke. Competition was stiff and one of the ideas that emerged to set local papers apart was syndicated columns – paying big money to celebrities and selling their stories to just one newspaper in each of hundreds of cities and towns for simultaneous publication. Syndication offered newspapers a way to stand out in the crowd for little investment – if the draw was right.

In 1915, Mary Pickford was the perfect choice for syndication, and she was intrigued by the possibility. But how would she have the time to turn out five 500-700 word columns a week? There were publicists even then, but could they capture the voice she wanted to present? Mary and her mother Charlotte agreed there was one person who could do the job– and that was their friend Frances Marion.

Frances had just signed with World Studio in Fort Lee, New Jersey for $200 a week which made her the highest paid screenwriter in the business. Mary didn’t yet have the contractual right to choose her own writer or director so she was not in a position to hire Frances full time, but Daily Talks would be a great excuse to get together frequently to review what had been written and to discuss future ideas. Mary was paid $1,000 a week and Frances made $50, but she later claimed to “love the experience.”

Always practical, Frances based herself in the smallest room at the Algonquin Hotel, bought a used car and hired an old San Francisco friend to drive her back and forth to Fort Lee which allowed her to work throughout her commute. She was turning out two to four short scenarios a week, so why not five columns as well? Her background in advertising and as a reporter helped her deduce what people wanted to hear, and she knew Mary so well it was easy to find her voice.

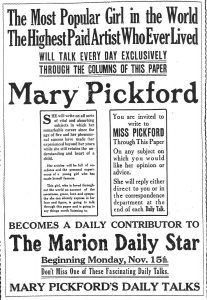

Subscribing newspapers headlined Mary as “The Most Popular Girl in the World” and “The Highest Paid Artist Who Ever Lived,” but the secret to the success of Daily Talks was the simplicity and sincerity at the heart of the columns. Mary was portrayed as a young woman with clear values: family came first, followed quickly by friends and community. The same backbone of steel and spunky character that emerged in her films came through in the columns. Her words of wisdom were dispersed with a velvet glove and never became preachy.

Subscribing newspapers headlined Mary as “The Most Popular Girl in the World” and “The Highest Paid Artist Who Ever Lived,” but the secret to the success of Daily Talks was the simplicity and sincerity at the heart of the columns. Mary was portrayed as a young woman with clear values: family came first, followed quickly by friends and community. The same backbone of steel and spunky character that emerged in her films came through in the columns. Her words of wisdom were dispersed with a velvet glove and never became preachy.

Through Frances’s pen, Mary dispensed helpful beauty secrets, advice on friendships and memories of her “happy girlhood” five days a week. They often began almost conversationally as in, “The other day I ran into an old friend” or “I received a letter that reminded me….” The power of positive thinking, individual responsibility and the importance of contributing to others were promoted in a wide variety of ways. The movement to create nursery schools was supported and “melting pot neighborhoods” encouraged. The columns warned young women against spending too much time on external beauty and assured them that they would find their calling. Sometimes Mary doled out financial advice and advocated not wasting money on “foolish trinkets.” Yet she also pointed out the pitfalls of being “penny wise and pound foolish,” citing the example of the young woman who walked 20 blocks to save a nickel on bus fare, but wore out a pair of shoes that cost a dollar in the process.

Young women and housewives were clearly the principal demographic. In most papers, the column ran on the women’s page rather than the entertainment section, and readers were encouraged to write in their questions to Mary. While a line or two response ran at the end of many columns, they were usually addressed only to initials and vague enough to appeal to many.

Daily Talks ran for a little over a year beginning in November of 1915, but the columns turned out to be much more than extra publicity and income. In fact, Daily Talks were life changing for Mary in two ways.

In the process of creating the columns, Mary and Frances became so close they could finish each other’s sentences. Their friendship and their trust of each other rooted the smooth working relationship they shared when they returned to Los Angeles together in 1917, after Mary had succeeded in acquiring the right to choose her own writer and director and Frances was headlined as “Pickford’s exclusive screenwriter.” Together they began molding the characters Frances adapted for Mary such as the Poor Little Rich Girl, Stella Maris, Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm and Pollyanna over the next few years and secured Mary’s lasting fame.

In the process of creating the columns, Mary and Frances became so close they could finish each other’s sentences. Their friendship and their trust of each other rooted the smooth working relationship they shared when they returned to Los Angeles together in 1917, after Mary had succeeded in acquiring the right to choose her own writer and director and Frances was headlined as “Pickford’s exclusive screenwriter.” Together they began molding the characters Frances adapted for Mary such as the Poor Little Rich Girl, Stella Maris, Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm and Pollyanna over the next few years and secured Mary’s lasting fame.

And because Daily Talks had presented Mary as a young woman who had faced poverty and adversity but always found the silver lining, readers felt they really knew her off-screen as well as on. They could relate to her and believed she could relate to them. The result of this emotional connection was witnessed when fans poured out by the thousands to see her in person when she toured the country selling war bonds. And there can be little doubt that the goodwill that the Daily Talks helped create resulted in her fans not only forgiving her, but actively rooting for her to find true happiness when she divorced Owen Moore and married Douglas Fairbanks.

Here is a sampling of Mary Pickford’s Daily Talks, beginning with the first one on November 15, 1915 and then some from April and May 1916 covering a wide variety of topics.