The Pickford-Fairbanks Studio 1928 by Laurence Irving

Laurence Irving was a renowned book illustrator, painter and theater set designer living in London when his friend, the playwright and screenwriter Eddie Knoblock, recommended him to Douglas Fairbanks. Mary Pickford and Fairbanks were visiting London in May of 1928, but Doug was also preparing for his next film, The Iron Mask. He was in the market for a great set decorator so he cabled Irving, asking him to come to the Hyde Park Hotel and bring “examples of your work.” At this point in their careers, Fairbanks and Pickford were huge international stars, mobbed everywhere they went, and unable to travel without security. Yet when a nervous Irving showed up at Fairbanks’s hotel room, carrying as large a portfolio as he dared, he found the star in the bathtub. Fairbanks acted as if nothing could be more normal and within a few hours had charmed Irving into agreeing to come to America to design the sets for The Iron Mask. Leaving his wife and children in London, Irving met the famous couple in Naples a few days later and set sail with them.

Laurence Irving was a renowned book illustrator, painter and theater set designer living in London when his friend, the playwright and screenwriter Eddie Knoblock, recommended him to Douglas Fairbanks. Mary Pickford and Fairbanks were visiting London in May of 1928, but Doug was also preparing for his next film, The Iron Mask. He was in the market for a great set decorator so he cabled Irving, asking him to come to the Hyde Park Hotel and bring “examples of your work.” At this point in their careers, Fairbanks and Pickford were huge international stars, mobbed everywhere they went, and unable to travel without security. Yet when a nervous Irving showed up at Fairbanks’s hotel room, carrying as large a portfolio as he dared, he found the star in the bathtub. Fairbanks acted as if nothing could be more normal and within a few hours had charmed Irving into agreeing to come to America to design the sets for The Iron Mask. Leaving his wife and children in London, Irving met the famous couple in Naples a few days later and set sail with them.

Their train trip across country was a revelation to Irving who had never been to America before, and his firsthand account of his arrival in Los Angeles and first visit to the Pickford-Fairbanks studio gives us an insight into movie making in 1928 as well as the personalities of the studio’s owners.

At Pasadena Station a horde of liege men and women and loyal subjects welcomed their king and queen safely returned from a crusade to win the hearts of Europeans… Doug handed me over to his eighteen-year-old son, “Junior.” As the crown prince of Hollywood, he had a sophisticated poise beyond his years. He had, of course, hereditary right of entry into the film studio and had already made the most of it. …

At Pasadena Station a horde of liege men and women and loyal subjects welcomed their king and queen safely returned from a crusade to win the hearts of Europeans… Doug handed me over to his eighteen-year-old son, “Junior.” As the crown prince of Hollywood, he had a sophisticated poise beyond his years. He had, of course, hereditary right of entry into the film studio and had already made the most of it. …

At the wheel of a powerful two-seater coupé, Junior, with an engaging detachment, concluded an informative and wryly humorous prologue of the motion-picture pageant in which I was to play a minor role. Of that drive I remember only the succession of gigantic roadside advertisements in dazzling white frames that made me feel as though I were being whisked through an exhibition of pictures painted by a prolific artist with impressive vulgarity. Never having visited Spain or Italy, the Mediterranean houses and pseudo-estancias struck me as original and picturesque and complementary to the brown, arid hills on which they were artfully perched by real estate dealers. All too soon we turned off Hollywood Boulevard, down a street overshadowed by a wall of buildings, and drove through steel gates, guarded apparently by a Texan philosopher and his Alsatian dog, into an enclave where soon I would have to justify the fabulous expense of my transportation thither.

In its centre stood three studios and the carpenter’s shop, each like an outsize airplane hangar. On two sides these structures were enclosed by buildings that met at right angles made by Douglas’s and Mary’s headquarters, their purposes and uses contrary for all their contiguity. Douglas’s dressing room, in effect a hall with an ever open door, led to a steam bath and a cold plunge. To Douglas, privacy was a deprivation. At all hours members of his court and visitors were welcome—at their own risk. For beside his dressing room table was an armchair into which the unwary, conscious of the privilege of his warm invitation to take a seat, sank in prospect of an intimate chat with their distinguished host, only to leap from it with a yelp of dismay as their posteriors tingled from an electric shock galvanized by a switch concealed under his dressing table. This hospitable snare, eagerly anticipated and relished by an audience delighting in practical jokes of any kind, betrayed, perhaps, his Teutonic ancestry, akin to the ponderous pranks played by Edward VII on his long-suffering courtiers.

In its centre stood three studios and the carpenter’s shop, each like an outsize airplane hangar. On two sides these structures were enclosed by buildings that met at right angles made by Douglas’s and Mary’s headquarters, their purposes and uses contrary for all their contiguity. Douglas’s dressing room, in effect a hall with an ever open door, led to a steam bath and a cold plunge. To Douglas, privacy was a deprivation. At all hours members of his court and visitors were welcome—at their own risk. For beside his dressing room table was an armchair into which the unwary, conscious of the privilege of his warm invitation to take a seat, sank in prospect of an intimate chat with their distinguished host, only to leap from it with a yelp of dismay as their posteriors tingled from an electric shock galvanized by a switch concealed under his dressing table. This hospitable snare, eagerly anticipated and relished by an audience delighting in practical jokes of any kind, betrayed, perhaps, his Teutonic ancestry, akin to the ponderous pranks played by Edward VII on his long-suffering courtiers.

In contrast Mary’s bungalow had the cloistered calm of a nunnery where its Mother Superior welcomed only faithful friends and business associates in awe of her perspicacity. There Mary, when not herself filming, spun daily from the threads of her talent as an artist and femme d’affaires the web of financial security for herself and her dependent relatives. Having been the family breadwinner since she was five years old, industry and thrift had become as obsessive to her as her faith in Christian Science.

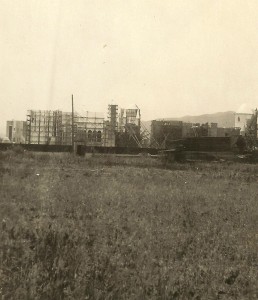

Beyond the studios was a vast open space, “the lot,” which from a distance appeared to be the relics of a world fair exhibiting every style and period of architecture known to man—a jumble of facades of stone, marble tiles, and brick skillfully rendered in plaster on frameworks of timber and chicken wire. There were the recognizable backgrounds of long-remembered films preserved intact by the perpetual sunshine until they outlived useful adaptation and were demolished to make room for new productions. Though more substantial than stage settings, each was truncated to the limits of the camera’s lines of sight, their jagged silhouettes reminding me of a shell-torn Belgian town.

Beyond the studios was a vast open space, “the lot,” which from a distance appeared to be the relics of a world fair exhibiting every style and period of architecture known to man—a jumble of facades of stone, marble tiles, and brick skillfully rendered in plaster on frameworks of timber and chicken wire. There were the recognizable backgrounds of long-remembered films preserved intact by the perpetual sunshine until they outlived useful adaptation and were demolished to make room for new productions. Though more substantial than stage settings, each was truncated to the limits of the camera’s lines of sight, their jagged silhouettes reminding me of a shell-torn Belgian town.

Excerpted from Laurence Irving’s Designing for the Movies: The Memoirs of Laurence Irving, published by Scarecrow Press in 2005.

– Cari Beauchamp